Improving STEM Careers Through Youth Outreach Programs

Electrical and computer engineering department working with community partners to integrate data science into K-12 education

"Severe" or "crisis levels" are how many experts describe the talent shortage in science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, careers that is expected to hit the U.S. labor market in the coming years.

While people have been working on addressing this for decades, the issues pervade and viable solutions have been lacking — until now.

The College of Engineering is taking a new, novel approach to address the STEM labor shortage and increase diversity in STEM careers. Their method: working with community partners to integrate data sciences and other important areas of STEM disciplines into K-12 education.

"What we want to do is: less talk, more action," said Professor Zhi Ding in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. "The problem we are trying to address is clear. There is an acute shortage of STEM-based talent. It is a big problem. Top level leaders in government and elsewhere talk a lot about it; but we, at the grassroots level, are reacting to a problem with an underground solution."

Regional Collaboration

In collaboration with a UC-wide interdisciplinary conglomerate housed at UC Davis called CITRIS and the Banatao Institute, the college is partnering with local elementary and high schools to create a series of programs, workshops and courses that are focused on exposing kids and teachers to data sciences. They are also working with teachers to integrate data sciences into the Common Core curriculum required by the State of California.

This new approach is needed because current methods of teaching are not keeping pace with the advancements of technology nor the demands of the workforce. For example, there is a deficit of one million highly skilled workers in the semiconductor industry, according to Deloitte, yet UC Davis researchers have discovered there are no high school courses on introducing basic concepts of semiconductors in the Sacramento and Yolo region. Semiconductors are critical ingredients in microprocessors, memory chips, integrated circuits, sensors and other intelligent systems.

To compensate for where curriculums fall short, a frequently used approach is to teach children basic coding through extra-curricular activities or camps. This approach doesn't work, according to Ding, because "coding is really boring for a lot of people," and it does not teach the skill set that is most applicable to many STEM courses or careers that students may face later in life.

"Computer coding does not teach problem solving," he said. "And problem-solving skills are what we really need in STEM careers."

Ding has partnered with Saif Islam, director of CITRIS and the Banatao Institute and professor of electrical and computer engineering, to work with area schools to help train teachers, inspire the students and modernize the curriculum.

Teach the Teachers

In the summer of 2022, the college partnered with CITRIS to host workshops to inspire teachers to cover topics that are more relevant to modern college courses and real-world applications in STEM, such as data sciences. They then worked with teachers to help them find teaching examples to correlate to what they observed in UC Davis research labs during the workshops.

Additionally, faculty at UC Davis analyzed a college-level introduction to data science course and then paired it with applicable common core concepts. They then gave all the teachers concrete lessons they could use throughout the year that both taught data sciences to the students and adhered to the requirements of the Common Core curriculum. Teachers who were involved enjoyed the programming.

"UC Davis wants students to be ready to enter college and choose majors that will require the use of data science," said Bruce Roberson, a former math teacher in Stockton School District who was a community partner on the project. "They want to provide as much support as possible to ensure that more students can choose majors that will provide a high wage which are fields that require competency with data science."

INSPIRE students

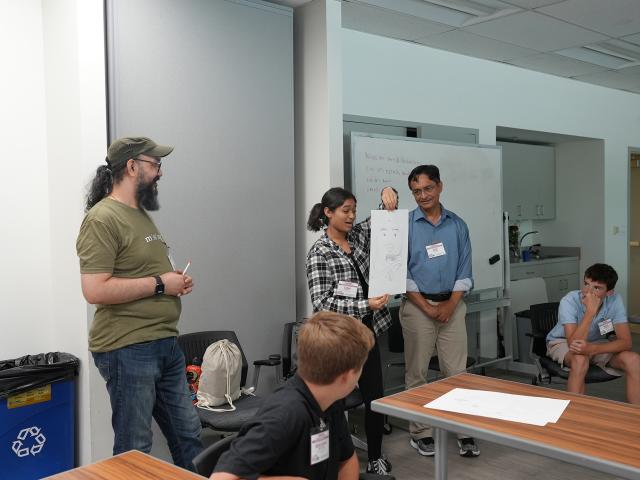

This past summer the college and CITRIS also hosted engineering summer camps for high school students, called INSPIRE, which stands for Incubates and Nurtures Scientific Pioneers through Innovation, Research and Education. At the camp, 25 high school students came to UC Davis to learn engineering concepts through hands-on teaching exercises, be exposed to college-level laboratories, and hear from engineering experts on various careers or areas of research that they could explore. Based on testimonies from the students, the camp's workshops were impactful.

"Thank you for assembling what has been the most fun AND knowledgeable three days I've ever been through. I never would have thought that the calculus I'm learning in high school would pan out to have such a large impact on the world," said one student. "This workshop let me realize how much more I want to learn, and what I can do/study to achieve a successful career that I also enjoy participating in."

Plans are in the works to expand the INSPIRE program next summer to possibly include workshops on semiconductor microchips, future drone technology and climate-resilient agriculture technology, robotics in health, and even half-day workshops at a national center housed at UC Davis that uses light to detect cancer and solar-cell making in the microfabrication facility (Center for Nano-Micromanufacturing or CNM2).

Engaging with the Public

In addition to hosting events at UC Davis for local teachers and high school students, Islam and Ding also went to area high schools for face-to-face meetings with educators, even going so far as to attend class to get a real sense of what it is like for the teachers. Although it takes considerably more time to run the program this way, both Ding and Islam say it is worth the effort because it helps build relationships of trust.

"We are not going to go in there and tell the teachers, 'Hey, you don't know what you are talking about.' Our approach is to develop tools so they can work this out," Ding said. "We are trying to build an alliance between teachers, principals, UC Davis faculty members and students. We work with them hand in hand."

Approaching the project from a stance of listening and collaboration also influenced its ultimate success. Not only do UC Davis faculty have allies who can help execute the project, but the resolutions they develop are more likely to succeed because of the input of the people who will have to enact them. For example, the team did not know about the Common Core restraints when they first started the project and had to adjust to align the new programing to work within the Common Core standards that teachers have to follow.

"We try to provide solutions to help with the problem; but, at the same time, we want to know, are we doing the right thing? We're not saying, this is the solution. We are working together to find the solution," Ding said. "We want to understand the critical needs of the community, what's important to them, and what are the constraints or obstacles."

Changing the system to break the cycle

Ding and Islam are hopeful that grassroots programs such as these will help break "this vicious cycle of socio-economic disparity" among underserved communities and improve diversity in the STEM fields. Their goal is to lay a foundation of success from which they can garner larger grants and national funding to scale up the program to include more schools locally, regionally and nationally.

"The only way to handle this problem is to invest in education in a way that will have an impact, we have to think about how we can do it differently," said Ding, adding that he was inspired to act after the death of George Floyd. "We are educators, and we want to see others succeed. Let's do something. Then we can provide inspiration to communities, school boards and parents with our progress. Because it does take a whole village to fix this problem. But we can play our part."